NB: I want to say straight up that these opinions are mine. Not the company I work for, nor any Mental Health Service Provider for that matter. I am a helpline counsellor, coach and workshop facilitator in the area of mental health, but that doesn’t mean I expect to get it all right. You may jump for joy in agreement with some of my points and have serious trouble with others. But the nature of talking about something as complex as mental health – especially at the cultural level – means that is often messy, political and subjective. Try as Psychology might over the last century to become the new Physics, it is 100% a human science. Coming up with a fixed set of answers for the human spirit is like nailing down what makes a poem well-written or a snow-capped peak resplendent. But it bears pointing out that I am no expert, no Masters Degree holder, no Registered Psychologist. Just someone who has heard my fair share of people’s stories.

And one who needed to share himself.

There is a lot of talk these days about the exponential rise in mental health issues, particularly among our rangatahi where mental distress has doubled in the last decade. Mike King has pronounced the mental health system ‘broken’ and he’s right. We require more and more for our young people to be at the point of suicide before they are taken in and given even the barest resources. This is unacceptable and as a helpline counsellor, it feels as if we’re aboard the sinking Titanic with the captain and crew pointing at the full life boats to explain the disaster.

But why is the ship going down in the first place?

I’ve heard many people within the field talk about the effect removing the taboo on mental health has had on people admitting they are struggling or the fact that we are simply better than our 1950’s counterparts at measuring it. While both true and worth celebrating, assuming this is all there is to it risks lulling us into the false belief that society is doing just fine as it is and all we need are more counsellors freed up.

As long as humanity has existed, civilizations have risen and fallen. Despite enormous progress in this one, there is absolutely no reason to assume that it will evolve in ways that increase the wellbeing of the people or planet that constitute it. Make no mistake: If we are experiencing a sea change in understanding stress and talking about mental health in the developed world (and I believe we are), it is because modern society has reached a crisis point of gargantuan psychological scale.

For Mental Health Awareness Week, I am sharing some of the main reasons for this crisis point that I’ve learned from 3 years of counselling and training New Zealanders in the mental health space and what we can do about it:

1. In the midst of pain, we forget we are more than what happens to us.

More than anything else, I believe it’s our decisions, not the conditions of our lives that determine our destiny.

Tony Robbins

It is a controversial yet persistent idea that people who are depressed or anxious must take some responsibility for it themselves. Of course, there is just no way that people consciously choose suffering from day to day or that there aren’t biological factors that predispose you to it. After all, what possible reason could someone have to wake up and not ever want to get out of bed? But after experiencing my own and the hundreds of others’ pain, I can also tell that from time to time, sitting in our suffering may be preferred.

There are a few reasons for it, in my view. Maybe we haven’t had our needs met from when we were tots. Maybe our worldview has been so ravaged by abuse or neglect or how sick the planet is or a job that crushes the essence of who we are, that we just can´t see the point in trying anymore. When we are depressed the head is down, the shoulders hunched and every offer of help rings wooden: empty words falling on ears long accustomed to disbelieving the facts that come through them. After all, how could we expect one conversation ‘at the bottom of the cliff’ to compete with thousands upon thousands of other experiences up top where we have been routinely let down by the cosmos and the broken people that inhabit our corner of it?

Not one of us has total control over what happens to us or the thoughts and feelings that result but – and this idea is seriously falling out of favour – we do have control over how we respond to what those feelings scream about us and the world. Even if your outlook entails a God, or ancestors, or spirit-self…we may surrender ourselves to their will and graces but in the end it is us on the journey. Whether from this plane or another, we will always need major support to stand up and take those initial, shaky steps but we must be the ones to move. There is nothing wrong with not feeling right in this world. If I experienced total sanity under these conditions I would hope you’d be concerned! There are a million different ways now to feel battered to within a psychological inch of our lives. To experience shame. To feel lifeless, the light of our willpower waning. In a lot of ways, remaining chronically helpless or depressed is the path of least resistance and even ´logical´ in it´s own way – our brain doing what the brain does to keep us safe.

Think of the Mama Grizzly and her victim who lies dead still as she approaches:

“If I don’t move, I won’t feel the pain when it comes”.

I have to admit, I grow desperate when I hear about how many of our people – young and old (and even our pets!) – are being adminstered medication for their mental health. While a crucial measure for many and a must-needed platform for therapy to work, I am increasingly concerned we are outsourcing the responsibility for sickness in the culture to individuals. The scores of young people who ring me and insist no type of medication has done anything for them in years of trying it, speaks for itself. Our species has not suddenly been beset by chemical imbalance in every other brain. Nor are our kids suicidal from an overdose of hormones. Myths such as these are the desperate pleas of a medical worldview way out of its depth. Today, we are literally surrounded by threats to our needs from birth – environmentally, in artificial institutions designed for economic rather than community gain, and being brought up by parents with mental health issues themselves. Add to this potent mix a body designed for taking death-defying action when its survival feels threatened, and you have yourself a mental health emergency.

Only now the Grizzly in the forest has become our spouse yelling – which reminds us of the parent that abused us – or the threat of being made redundant amplifying early feelings of abandonment, of not ever feeling good enough. The same neural technology that put us into fight, flight, fright for millennia has not folded itself away now that we have wifi and Mcdonalds. It continues to respond to threats just as voraciously as it once did for cats and snakes when we were in the trees. The difference is that with modern stress, we continue to suffer long-lived surges of adrenaline and oxytocin throughout the day and (for more and more of us) at night as we lie restless, long after the initial “snake” (partner arriving home, boss arranging a meeting with us) has slithered away.

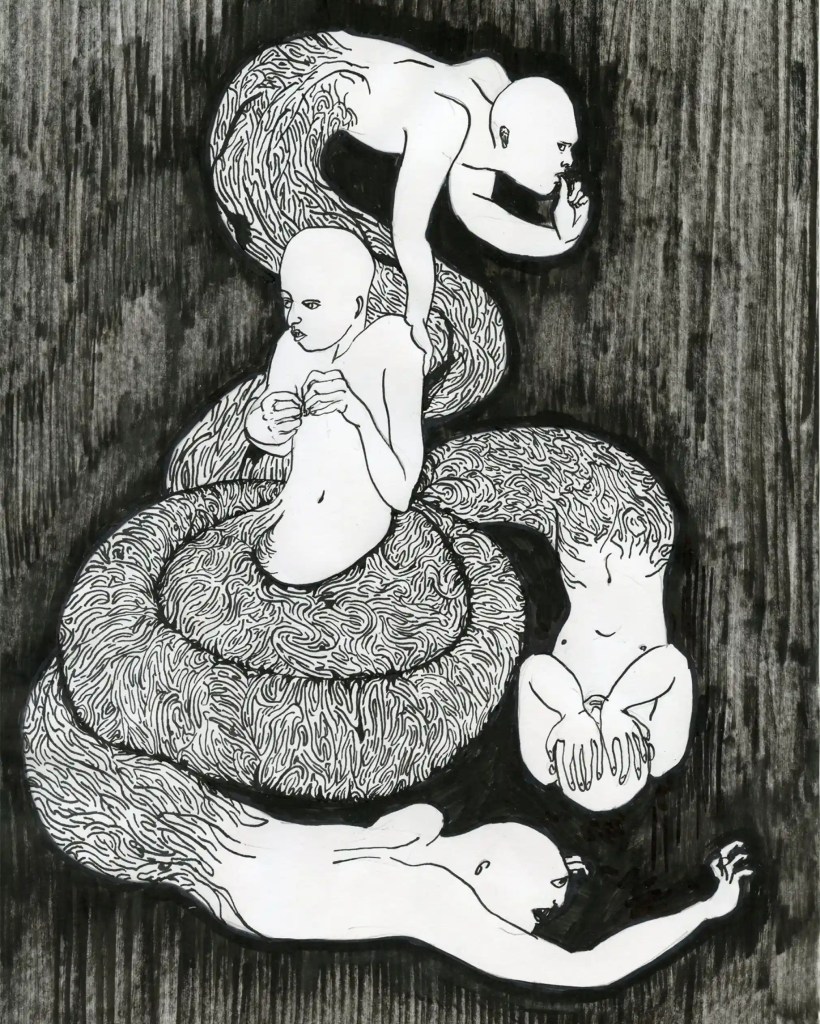

At the extreme end of this process lies helplessness and despair. To ‘figure it out’ and so the thing doesn’t happen again, the mind gets on the hamster wheel and spins for all it’s worth. Most of us do so in our heads and an increasing number of us are learning to do so with a counsellor or the people we love and trust. We may either need to justify what happened, get some insights into our pain or exorcise the demons that bind us. This is natural and as a nation we need more of it. More rarely, the static sharing of our story over the long term can also become a ritual: a commemoration ceremony where nothing is shifted and the brain justifies its existence with something terrible yet familiar to process, even as it dominates our lives and those of the people who bear witness. It’s important to note that this isn’t just in speech, but in action too. All of us will, in some small way, be recreating the earlier tragedies that molded us in our relationship with others and the truths we whisper to ourselves about the real nature of the world and our selves. In the case of a lot our young people, they will simply shut down their whole internal program – the good and the bad – just to escape the truly ugly. Self-harm and suicidal ideation then take the stage because in spite of all of our pharmaceutical or emotional innovations we simply haven’t devised the means to selectively numb our feelings. When we blot out the negative, we run the risk of blunting the positive too.

What then, can be done?

I have to admit that on an individual level, I have only clichés to offer you. But they are clichés because they are true: deep universals that swim in the subterranean currents beneath our sick culture. And although I am priveleged in many ways, I think it’s always best to start with myself.

I have struggled with bouts of what could be called anxiety and depression since adolescence and have a pretty good understanding of why that might be. But I never had what I would call serious mental health problems until I experienced a breakdown off the back of a relationship break up in early 2019. At the time, I decided it would be a good idea to walk it off on my own on Te Araroa: The National Walkway which spans the length of the country from Cape Reinga to Bluff. My first bit of advice would be not to do this (haha!), or if you do decide on just such a major catharsis, wait until you are somewhat out of the woods yourself. Connection is key, and even if we despise the car we are driving, it’s very often not in our best interests to take our hands off the wheel entirely. We will need some scaffolding and distractions in the form of walking our dogs, having some moderate amount of contribution or work and familiar hearts and faces that we can navigate towards when seas get rough.

In my case, COVID was my saviour. I returned home for lockdown, having hitchhiked half of the South Island for three months. It had done nothing for me. In fact, stubbornly doubling down in my self-isolation made sure that I returned in far worse shape than when I’d left. Lockdown was a blessing in disguise. I moved back in with my parents and sister, and proceeded to rebuild my psyche. I wrote out the things that used to make my life worth it – ten of them – and blue tacked them to the celing so when I woke up to my racing heart and jello-mind, I had a mantra to cycle through. Opening my arms, I would pray as I hadn’t in a decade since leaving the spiritual framework of my upbringing. I had reached the threshold of what I knew I could handle and sailed well beyond it. My intellectual objections to God – the colonial evils, the bigotry, the trapped minds – fell apart completely in the face of that central burning truth: that I felt utterly beyond the reach of any earthly help. And I was terrified that nothing could change that.

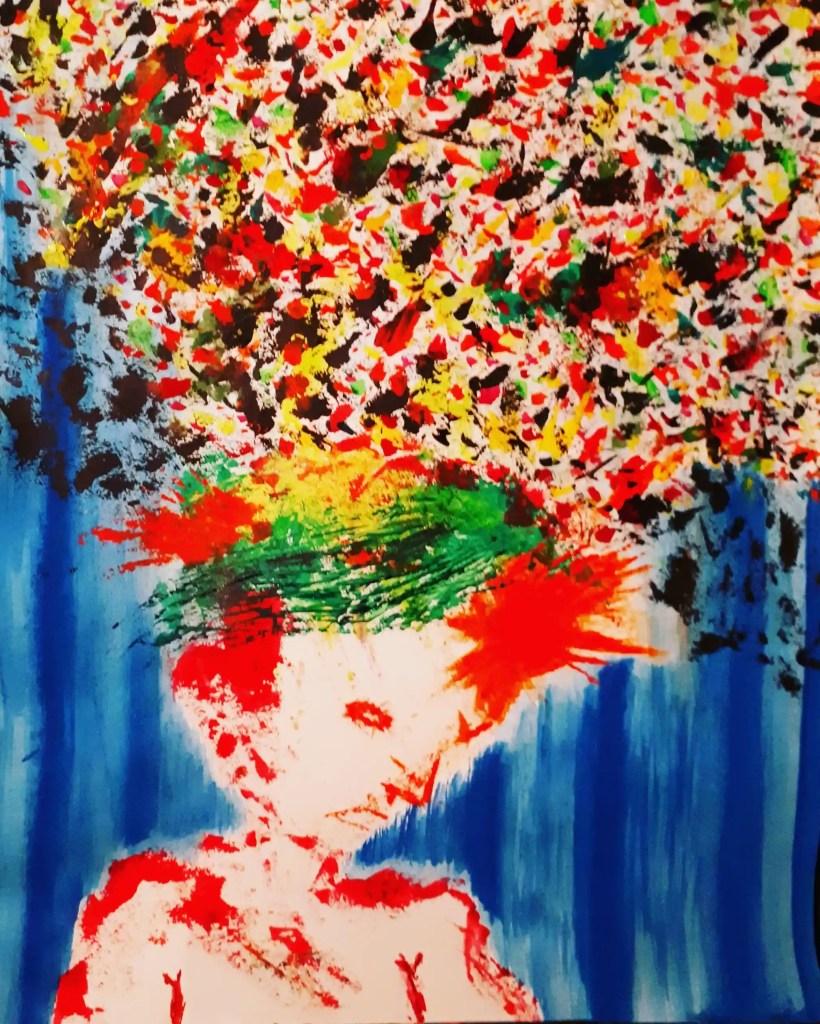

Every time I tore myself out of bed felt like lifting an olympic grade bench press. My body was made of lead; my mind a cocktail of confusion, guilt and almost constant despair. I picked up my guitar, sat in the sun on the grass and sung anything I could. Most often worship songs I thought I’d forgotten. Sometimes Bob Marley. Others the songs I’d grown up listening to. I guess my spirit hoped that returning to those song-stories of my youth, I could claim some sort of anchor out of the past, a time when I still wanted to live in the world and with myself. I would then organize my sometimes bemused but mostly awesome family into jump jam sessions (with neighbours watching on as we stumbled through the Ketchup Song) and pilates on the lawn. We then talked about our dreams, and expressed what we saw in them before opening the floor for people to offer their interpretations (I told you I was desperate!)

Whenever I could drum up the will power I was journalling like a Founding Father drafting up a Constitution. In the evenings, I would reflect on what had gone well and what I would do differently if I had the chance (which turned into a second ceiling-list of “Things to Focus On”). My intentions in the mornings were to word-vomit whatever I woke with in my head, wallow through what I was grateful for (often bugger-all), and proceed to set some modest goals for the day. The goals were administrative mostly but included self care moments and creative projects that became my lifeblood when nothing else touched the sides. I was writing a blog series on my hitchhiking adventures disclosing next to nothing of the mental agony I’d experienced as soon as I arrived at a new place or was left alone with my thoughts. In the spirit of channeling my own suffering into helping others during Lockdown, I wrote a list on my blog of things that helped, ommitting the countless days when nothing could. I videoed myself as a comedic new age guru “Hernandez’ locking down in a cult with his ‘pilgrims’, the narcissistic values of whom I partly blamed for my tumultuous relationship. I began writing the real story of my relationship and gut-wrenching aftermath in a novel version which, while bitterly dark, was one of the rare times I felt okay in my body – creatively rather than cognitively processing what had transpired.

Cognitive processing happened too in the form of my journal and in weekly online counselling I organized through the website betterhelp as it was a lockdown and – with internet and room in your income – there is no waitlist to get help. I explored the dynamics I was barely coping with (confusion, isolation, extreme discomfort occupying my body and mind) and told the story of my journey to Robert. He listened to me – crucially without judgement. It sounds like such an obvious thing when you’re in the clear but when you’re in it, boy…having someone listen to the whole of your bitter, hopeless inner world and not turn away in horror feels like you are in the immediate grace of God. I am convinced that being heard and acknowledged and that person not flinching is 80% of the work. Organizing the therapy, not cancelling last minute and remembering to treat yourself well in the aftermath of a session are the hardest parts. The rest floated along on a river of incremental change. I found that if I allowed even a smidge of belief that my life was redeemable and noticed the microscopic ways my mind felt more inhabitable over time, the progress was natural. But I have to say, it takes time. I think it was a full two years before I felt myself again. And of course, it wasn’t ‘myself’ was it? It was somebody permanently changed, and not just in the ways I grieved but in the ways I was humbler, more resilient and more connected to the people I’d taken for granted throughout my 20’s.

I worked a handful of hours as as a counsellor on the helpline, grateful for the brief escapades into other people’s heads. I cooked dinner, did simple chores and watched films that told the right stories. Mostly I tried to feel okay from moment to moment. I do not wish to make this out as a “how-to”. I was utterly miserable, even after months of this. I still can be. I had sleepless stumbling along the beach in storms where I wondered if my body would always feel as if it was trying to eject my spirit for good. I was never actively suicidal but for the first time in my years of talking people out of it, I finally understood the motive. But even on the days when I felt like I’d slid back entirely to the beginning, I chose to hope. Through the facial ticks and nightmares, and through the inability to focus on any one thing. The insomnia, the missed weddings, the bailed-on zoom calls. Through the feeling like I had been through the wash and couldn’t dry, my parts a fizzing electrical fire waiting to happen, and the constant sensation that I had damned me and my body to a living hell, I chose to believe – most times completely in the abstract – that the next day could be slightly different. Sometimes it wasn’t, sometimes it was. And when it was, I was priveleged and brave enough (God knows how) to make a note of it and settle back in for the next go-round.

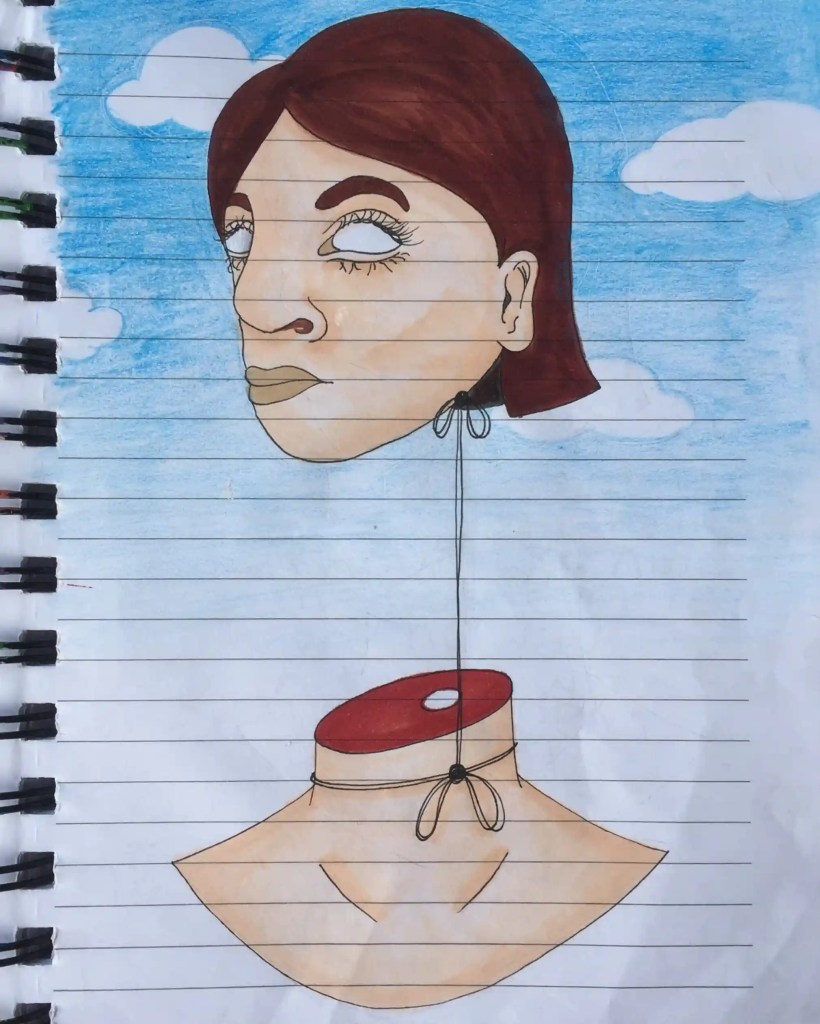

I wanted to write that I can look back on it now from a stronger place but I don’t know if ‘stronger’ covers it. If I’m honest, ‘aware of my vulnerability’ feels like a better description. Maybe that’s a nice defintion of strength, or at least courage: a healthy respect for my fragility and acting in spite of it. I am both in awe of how completely I was engulfed by misery and emboldened by how I managed to crawl back to wholeness. As mentioned, I am not the same. Some days, I think of it as if every cell was replaced as I died: a shedding of skin necessary to rehouse an ailing spirit. I am sensitive and responsive to my often massive emotional life, quicker to tears, intimately conscious of how my body affects my mind and vise versa, of my limits and egoic excesses: the blind spots where I routinely hurt others or myself and I believe, a slightly greater capacity to love. I could never have done it on my own. I know now that we are essentially social creatures and the central lie of the modern world, especially for our tāne is that strength is accomplished in isolation.

Baloney!

More than ever, I believe we don’t just benefit from but desperately depend on the collective presence of our loved ones and people who know us to steer us back on course, lovingly and without judgement. The two extremes of “they know their own truths – just leave them be” and “I can help fix this for them” are equally unhelpful. When we are flailing, we need acknowedgment, we need curious listening and then gentle offers of reflections and wisdom-giving advice. In that order. We don’t always know “our own truth” becasue sometimes when we are in pain we might not know which way is up and we actually need to outsource our sanity to balanced others who know and love us and who can see the situation for what it is.

Equally, nobody – island or not – is static in either their brokenness or wholeness! There has been the slow creep of the idea in psychiatry and pop psychology both that some people are just going to struggle no matter what and require a chemical intervention or lifelong attention. Our kids grab a whiff of this, connect it to the existential dread inherent to their stage of life, and conclude they are in that camp; that nothing can ever shift them into feeling okay. There has never – not climate change, not world war three, not COVID 19 – been a more dangeous threat to our philosophy: that we are essentially meat puppets doomed to the wiring we inherit or the traumas that happen to us, without our control. In reality, human beings and the events of our lives ebb and flow to lesser and greater degrees with the patterns of nature, Te Ao and Te Po, peace and disorder, joy and depression, cycles of productivity and low energy, seasons, weather events, and the tension between life and death itself. I suspect there may be caveats to this with trauma but I wouldn’t write it off in those cases either: the deeper the chaos, the more profound the renewal. And just because this moving and shifting is inevitable, doesn’t mean we are powerless to adapt to it. It just requires a deliberate, heart-led opening to what is arriving at the bend in the road.

We will need guidance and support to process trauma, anxiety and the helplessness that gives way to depression, but we will ultimately have to decide how much life force we can put into believing things can change; so that we won’t stay victims of a nervous system and self-consciousness that started with “Adam and Eve” in the Garden. It will require what feels like superhuman effort in most cases. But asking loved ones for help when we feel like a dead weight, exercising some responsibility for our inner worlds and even pretending to take care of ourselves will lead to better outcomes when we are feel chained to what happened. The sooner we reach out, the better too. Years of time and money, or even our lives can be saved by having ‘that conversation’ now instead of waiting to be brought to our knees.

In the West, we have come to treat ourselves appallingly. The sins of the fathers are the children’s to inherit and although in my view this has been in motion since the First World War, in no other generation is it clearer than the case of Gen Z. Know that you are worthy of help, again and again. Remember: two steps forward, one step back (even on the days when it’s three or four back). The highs can match the lows: open your heart to them when they begin to arrive, and they may well continue to. You have capacity you can’t imagine just now. And most crucially you are not the sum product of the chemicals in your head.

You are human. Impossibly fragile, and immeasurably strong.

If you or someone you know needs support:

- Find a Counsellor on the NZAC website or through your GP

- Anxiety NZ is a wonderful resource for learning about anxiety symptoms and some techniques for managing it which the volunteers can help over the phone with (0800 269 4389) (0800 ANXIETY) or anxiety.org.nz

- Use the ANZACATA Therapist Directory to find a Creative Arts Therapist near you

- Betterhelp provide online personalized and low-wait time counselling

- Youthline are a multimodal service for young people across text, phone, skype and face-to-face counselling (Free call 0800 376 633. Free text 234). They also offer programs in schools (topics like drugs, violence, relationships), communities (personal development and youth leadership/advocacy programs) and organizations (https://www.youthline.co.nz/programmes.html)

- Lifeline (call 0800 543 354; text 4357) can cover a range of needs with their ‘brief intervention’ model which is less about diving deep into the past to understand why and more about reflecting, validating, normalizing (soothing) then helping explore what the person’s next steps are while linking them to resources internal and external to the person’s life. Ring them for a chat! They would love to hear from you no matter how far along in your pain you are.

- 0800 211 211 (Family Services Directory: a directory of all mental health services in different areas of NZ)

- Insight Timer: A free meditation app with millions of recordings and users

- Calm and Headspace have great reputations as paid mindfulness apps

- Lifeline Connect provide training in workplaces for managing complex interactions with clients, as well as understanding stress, and promoting employee wellbeing through self care and external supports provided by the Lifeline Helpline